From a draft for a book chapter I am writing for the Politecnico di Torino. Individual figures have been imitted (chapter not yet published and may change).

Introduction

I was invited to speak and host a game design prototyping workshop at the second and third summer school at the Politecnico di Torino’s Castello del Valentino, in Turin Italy.

2018 Workshop

At the 2018 workshop, I gave a talk on Monday in the summer school “Cultural Heritage in Context, Digital Technologies for the Humanities”, 16-23 September 2018, on Virtual heritage and publication issues, “Virtual Heritage: Techniques to Improve Paper Selection”.

The lecture covered the basics and some of the issues of writing a scholarly paper in the research area of virtual heritage, (such as research challenges; important controversies, debates, issues; techniques to improve paper selection; suggestions to improve the field; publishing; and important journals in the field). It drew on issues I wrote in the book Critical Gaming: Interactive History and Virtual Heritage (Champion, 2015). It is a difficult field to write for as the reviewers could be drawn from computer science, cultural heritage, museum studies, usability studies (HCI), architecture, art history, and media studies.

I also ran a workshop on game prototyping especially for history and heritage games. This chapter will focus on the workshops run in 2018 and 2019, as the summer school gave me an excellent opportunity to test out some ideas to teach students how to design simple game prototypes that nonetheless could be modified and adopted into fully functional digital games.

The 2018 summer school allowed me to develop my theories of game design, how to teach the simpler components to students from architecture, art history and archaeology, who are interested in history and in heritage. I was particularly interested in developing the conceptual framework that I first made a rough sketch of for the students in 2018 and re-presented as a new diagram to the students at the 2019 class.

NB the slides from the 2018 workshop are still currently available at http://slides.com/erikchampion/deck-9/

I will concentrate on what I think will be of most interest to the reader, the core elements of the game design workshop, the groups that formed, and the game prototypes that resulted.

The Game Prototyping Schedule

The schedule for both years was roughly as followed (starting 8.30AM, ending 12.30PM).

- Introductions for all (10-20 minutes).

- Overview: games, gamification (50-40 minutes) finish 9:30.

- Discussion of technologies, methods + prototyping (20 minutes).

- Group suggest ideas (10 minutes).

- Short break/questions (20 minutes).

- Selection of teams (10 minutes) Finish at 10:30.

- Work on game ideas as prototypes, playtest solutions OR describe how Digital Humanities simulations could be gamified (90 minutes).

- Present prototypes/suggestions in class (30 minutes) finish 12:30.

I explained the basic concepts and issues of procedural rhetoric and game mechanics and suggested how Roger Caillois’ four forms (or modes) of game play could be used to construct a basic idea of how a history or heritage piece could be transformed into an entertaining and educational game. According to Caillois, games were (and still are) enticing players to compete, to imitate, to risk, or to overcome feelings of vertigo (and related bodily movement challenges). Games are engaging challenges (not only feedback rule-based systems).

The implied and accepted goal for the player is an essential component. What would be the goal of the player? Once we choose a site with cultural significance and hidden or less well-known features, we could apply one of these modes to the game as an interactive experience, decide on the core gameplay (repeated, characteristic action) that the player must learn to reach their goal, the core mechanics that moves the game along (to the next level or challenge or to its conclusion) and the types of rewards and punishments, affordances and constraints that would stand in the way or help the player.

Before designing a game, it is important to consider the components that make a game playable.

- What should be experienced and interacted with, as specifically as possible.

- Why create a specific experience in a game? (Our objectives?)

- Where will it be played? (What is the environment, the imaginative setting?)

- How to convey the experience of the site, artefact or model?

- Systems, methods, or findings leading to engaging learning experiences?

- Reveal what is unknown or debated (how knowledge is established or contested)?

- Interpretative systems or to test, demo, pose or test a scholarly argument?

- When will the player receive suitable feedback?

Once answers to the above questions are answered, the basic steps in designing the game are:

- Determine cultural, historical or archaeological facts and interpretations of the site or model that are significant, hidden, or otherwise appropriate, engaging or transformative to explore.

- Consider the environment it will be played in, not just the type of audience, together, alone, on a bus, in a lecture theatre, at a museum?

- Design a game rather than a virtual environment: choose a challenge (Roger Caillois’ modes of game experience or another appropriate theory), and how core game play affects and is affected by the modality of experience. Steps 2 and 3 also give us an idea of a setting and theme.

- Define the core gameplay, what does the player typically do? Does the game scale, changing in effectiveness and complexity over time? Increasing complexity keeps interest.

- Develop a reward and punishment system; how do the rewards and punishments interact with the core gameplay and move the game along (i.e. trigger its mechanics)?

- End meaningfully. What is the end state? How will the game mechanics help us get there? Does reaching the end state create an intentional specific reflection, knowledge development, interpretation, experience or other feeling in the player?

2018 Summer School Game Design Groups

During our workshop in 2018, the students separated into four main groups. Professor Donatella Calabi of Università Iuav di Venezia (Université IUAV de Venise), led a group who prototyped a serious game promoting a more serious and authentic understanding of Venetian culture to foreign tourists.

The second group, led by Professor Rosa Tamborrino, comprising at least three nationalities, scoped out a game designed to teach people the value of artefacts that were stored in Brazil’s national museum. A catastrophic fire destroyed much of the collection, and this game was designed to encourage people to explore and decide on the relative value of its holdings, in order to save the more precious and irreplaceable items before the fire destroyed them.

The third group, led by Associate Professor Meredith Cohen of UCLA, discussed how a serious game could communicate the building technology of Chartres Cathedral.

The fourth group, led by Professor Michael Walsh, from NTU Singapore, led a group exploring how the Saint George of the Greeks Cathedral in Famagusta, eastern Cyprus could be explored via a game.

2019 Summer School Game Design Groups

In 2019 I was invited to run the game prototyping workshop for a second time (Figure 8). The 2019 summer school was entitled “Learning By Game Creation: Cultural Cities, Heritage, and Digital Humanities” (http://digitalhumanitiesforculturalheritage.polito.it/). At the 2019 workshop, I ran a workshop on Tuesday September 3, on Gamification and Cultural Heritage. I also gave a lecture on Friday, September 6, on “Writing a Scholarly History Paper in the Digital Age.”

One group’s initial idea was to develop an environmental educational game for children visiting a museum or gallery. The children were given patchwork fragments representing different ecological zones and their mission was to patchwork their preferred city together to form an environmentally and ecologically pleasant city to live in.

A second group, both archaeologists, developed an underwater prototype platform-style game, where the player would descend levels of a submerged classical city when they managed to solve the clues.

Figure 10: Underwater archaeology game, Brazil: game, DH Summer School, Turin (September 2018).

After the first half-day we were given more time to develop game ideas, but ideally focussed on using archival material such as found in the National Museum of Cinema (Museo Nazionale del Cinema) Turin.

One group developed an augmented reality game for tourists who had an hour to spare exploring Turin, via their smartphones. The quest-based VRecord Phantasmagoria Backstage Access game would entice visitors, alone or in teams, to explore Turin’s historical buildings and there was the potential to role-play historical characters. High-scoring players could also be recorded on the museum website in a virtual hall of fame.

A second group developed another augmented reality game, PockèTO. This game was described as “A Treasure Hunt to Discover Turin.” It was a treasure hunt where teams of players can collect as many treasures as they like but they only had fifteen minutes to collect objects then forty-five minutes to “rebuild the city”.

A third group developed Lost in Time,, a two-dimensional quiz game, where the player was asked to help a historical character who finds himself in modern-day Turin, to find clues to help him to time-travel back to the past.

The fourth group developed the TO game, an elaborate boardgame with QR codes, where the players would be dealt cards and could scan the QR code to be given information about Turin’s historic movies.

Outcomes and observations

If I had the chance to run the workshop again, then I would suggest more coordination with the landscape appreciate and design workshop run by Dominica Williamson, Professor John Martin and Andy Williams. I believe there is great potential synergy in connecting history and heritage to outdoor explorations and to prototyping using local materials.

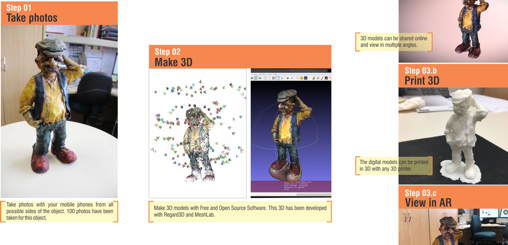

I would also develop more templates to show how simple games could be brainstormed, and link more directly to augmented reality and virtual reality prototyping tools. I say this even though I am convinced the paper prototyping and board game prototyping tools were very effective in assessing the immediate playability of the game, it would be very useful for the students to have access to tools to develop their own ideas in AR, MR and VR form after the course.

The workshops have also proved to have been wonderful for my research. My next book, Rethinking Virtual Places, may involve a discussion and photograph on game prototyping from one of the workshops. I have also been part of a project team awarded a national three-year grant, and my component will be to supervise a PhD student who will design and evaluate a game design framework for a state museum and a national museum. I have also applied for a four-year national fellowship on this topic. The success rate is very low but I have greatly enjoyed the experience writing it and the workshops were indispensable for testing my ideas, so I am very grateful to the organizers and students of the Summer Schools.

I also used the experience gained from these workshops to run a very similar workshop for the DHDownunder summer workshop at Newcastle University Australia, in December 2019, and it was very popular, all four groups designed interesting and engaging prototypes.

Finally, at least one student from the game design workshop, Manuel Sega, informed me that after the 2019 Summer School, he taught a very similar game design workshop in Colombia, South America. The topic was “what does Colombia need to play?” In all seriousness, I cannot ask for greater take-up than this. Thank you very much!

-Erik Champion

REFERENCES

Champion, E. (2015). Critical Gaming: Interactive History And Virtual Heritage (D. Evans Ed.). UK: Ashgate Publishing.