Impressed with Shawn Graham’s decision to blog a draft of his paper I decided to do the same … here is a draft of a more informal paper/article for <name of journal omitted to protect the innocent>, for a special issue/forum on games and archaeology.

Any issues, queries, suggestions, please let me know! Please remember, this is only a draft.

-Erik

Title: Bringing Your A-Game To Digital Archaeology: Why Serious Games And Virtual Heritage Have Let The Side Down And What We Can Do About It

Author: Ear Zow Digital

Wandering around museums or visiting art galleries and school fairs a relatively impartial observer might notice the paucity of interactive historical exhibitions. In particular there is a disconnect between serious games masquerading as entertainment and the aims and motivations of archaeology. Surely this is resolved by virtual heritage projects (Virtual Reality applied to cultural heritage) and interactive virtual learning environments? After all we have therapy games, flight simulators, online role-playing games, even games involving archaeological site inspections. Unfortunately we have few successful case studies that are shareable, robust and clearly delivering learning outcomes.

Early virtual heritage environments were low resolution, unreliable or required specialist equipment, with limited interaction. Games were and still are far more interactive and are arguably the most successful form of virtual environment, so it would seem to be a masterstroke to use game engines for virtual heritage.

Why have games succeeded where virtual reality has failed? In terms of consumer technology there is virtually no competition. Games are typically highly polished, focused products. Large and loyal audiences follow them and if they allow modding (modification of their content) then the community of fans will produce an enviable amount of content, useful feedback and grassroots marketing for the game companies. Virtual reality companies don’t have the loyal audience base, the dedicated and copyrighted content and technology pipeline, or the free advertising.

Game consoles are now the entertainment centers of so many living rooms, the game consoles and related games can last and be viable for ten years or more and in many countries the game industry makes more money than the film industry. Virtual Reality, by contrast, seems to move from hype cycle to hype cycle. The recent media blitz of head mounted displays is exciting and no doubt I will also buy one, but just like the earlier pretenders the technology has great promise but the inspiring long-term content only appears to exist in videos and artists’ impressions.

As interactive entertainment most computer games follow obvious genres and feature affordances (well-known themes, rewards and feedback on performance), they challenge people to find out more rather than telling them everything (a sometimes annoying and overloading aspect of virtual environments) and in most games learning through failure is acceptable (and required). And here lies another advantage for games over virtual environments: games offer procedural knowledge rather than the descriptive and prescriptive knowledge) found in virtual learning environments.

Most definitions and explanations of games include the following three features: a game has some goal in mind that the player works to achieve; systematic or emergent rules; and is considered a form of play or competition. Above all else, games are possibility spaces, they offer different ways of approaching the same problems and because they are played in the “magical circle” failure does not lead to actual harm, which allows people to test out new strategies. That is why, unlike other academics, I don’t view a game as primarily a rules-based system. I think of a game as an engaging (not frustrating) challenge that offers up the possibility of temporary or permanent tactical resolution without harmful outcomes to the real world situation of the participant.

Despite the comparative success of computer games, successful serious games and education-focused virtual heritage games are few and far between. The following preconceptions about games (and game-based learning) could explain why more interactive and game-like heritage environments have not emerged as both engaging entertainment and as successful educational applications.

The first and I think most common preconception of games is that they are puerile wastes of time. For an academic argument against this view, any publication on game-based learning by James Gee will provide some interesting insights, while Steve Johnson in Everything Bad is Good for You writes in a similar if humorous way on how games help hone skills.

Many critics believe games are only for children. Such a view would conveniently ignore the adult enjoyment of sports, but it also neglects the question of how we learn about culture. In the vast majority of societies around the world people learn about culture as children through play, games and roleplaying. Games are also an integral method for transmitting cultural mores and social knowledge. In “The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention (http://w hc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/) UNESCO specifically state they may provide assistance for informational material such as multimedia to promote the Convention and World Heritage “especially for young people.”

A related criticism of computer games is that they are only about fantasy. While it is true that some human computer interaction (HCI) experts see fantasy as a key component of games, fantasy is also a popular component of literature and fantasy provides a series of perceived affordances, the player is asked to let their imagination fill in the gaps. So perhaps thematic imagination is a more appropriate term. Fantasy creates imaginative affordances, we have a greater idea of what to expect and how to behave when we see fantasy genres and we are more willing to suspend disbelief. Fantasy helps induce narrative coherence and is a feasible vehicle to convey mythology connected to archaeology sites.

Games are not only about fantasy for many are also highly dependent on simulating violence. Yet some of the biggest selling games are not violent, for example Minecraft, Mario and the Sims series: the Sims. A more serious problem for my research has been when the real-world historical context to simulate is itself both horrific and hard to grasp. My objection to violent computer games is not so much that they simulate violence but that they don’t provide situations for the player to question the ubiquitous and gratuitous use of violence. Be definition computer games are good at computing options quickly so it is easier to cater for reflex-based challenges, stopping the player from thinking, from having time to reflect, but challenging them to both move and aim (coordinate) at the same time. And when mainstream game interaction is applied to virtual heritage and digital archaeology, the information learnt is not meaningful or clearly applicable to the real world and the skills developed are not easily transferrable.

Marshall McLuhan apparently once said “Anyone who thinks there is a difference between education and entertainment doesn’t know the first thing about either.” I have not found the origin for this quote but this saying is popular for a reason: many automatically assume entertainment is not educational or that to be meaningful, education cannot be entertaining. In the area of history this is a very worrying point, a recent survey of the American public found that while they were charmed and inspired by the word “past”, the word “history” reminded them of a school-time subject that they dreaded (Rosenzweig and Thelen, 2000).

Gamification could be the commercial savior for many educational designers but it has many critics. Fuchs ( 2013) explained gamification as the use of game-based rules structures and interfaces by corporations “to manage and control brand-communities and to create value”, this definition reveals both the attraction of gamification to business and the derision it has received from game designers and academics.

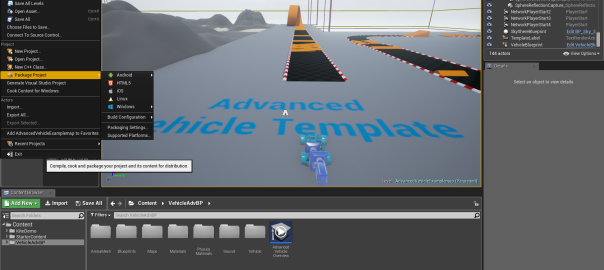

A more technical objection to using games for digital archaeology projects is that they can only provide low-resolution quality for images, movies and real-time interaction. With all due respect, game engines (such as Crysis and Unreal 4) and archaeological environments created in game engines (such as http://www.westergrenart.com/ or http://www.byzantium1200.com/) would challenge many CADD (computer-aided design and drafting) showcases. In 2015 the Guardian newspaper released an article declaring we are entering the era of photorealistic rendering (Stuart, 2015). Autodesk (the company behind the biggest CADD programs) have recognized the threat and now sell their own game engine. Even if CADD did produce higher-resolution and more accurate 3D models, what advantage would this offer over game-based real-time interactive environments where the general public is free to explore?

The last preconception or rather I should say concern about games is that they are not suitable for preservation due to software and hardware obsolescence. Game-based virtual heritage environments are not great as digital heritage, the technology does not last and the content is not maintained and updated. I agree this is a major problem, but the problem is more a lack of suitably maintained infrastructure than technology. In terms of usability research, there are very few surveys and tangible results that have helped improve the field but the biggest issue is preservation of the research data and 3D models. We still lack a systematic pipeline featuring open source software, a well-organized online archive of 3D models in a robust open format, globally accepted metadata and a community who reviews, critiques, augments and maintains suitable content.

Definitions vary but virtual heritage is not an effective communication medium and is certainly not a great exponent of digital heritage. Many of the great virtual heritage showcases such as Rome Reborn, or Beyond Space and Time (IBM) have been taken offline, use proprietary software, or have simply disappeared due to a lack of long-term maintenance. So there are very few existing exemplars and accessible showcases to learn from, (CINECA’s Blender pipeline: https://www.blendernetwork.org/cineca is an exception to the rule).

Many game engines can now export to a variety of 3D formats and run across a variety of platforms and devices. They can export VRML and now also WebGL so interactive 3D models can run in an Internet browser without requiring the end user to download a web-based plugin. Some game engines can dynamically import media assets at runtime; others can run off a database.

UNESCO recently accepted my proposal to build a chair in cultural heritage and visualization to look at these issues from an Australian perspective. We intend to survey and collate existing world heritage models, unify the metadata schemas, determine the best and most robust 3D format for online archives and web-based displays, provide training material on free open source software such as Blender and demonstrate ways to link 3D models and subcomponents to relevant online resources.

Conclusion: Archaeologists and Games Do Not Mix?

Archaeologists and suitable games could mix if games existed that leverage game mechanics to help teach archaeological methods, approaches and interpretations. As far as I know, archaeologists don’t have easy to translate mechanics for their process of discovery and understanding that we can transform into game mechanics to engage and educate the public with the methods and approaches of archaeology and heritage studies. And yet virtual heritage environments should be interactive because data changes and technologies change. Interaction can provide for different types of learning preferences and interaction will draw in the younger generations.

My solution is to suggest that rather than concentrate on the technology archaeologists should focus on the expected audience. What do we want to show with digital technology, for what purpose, for which audience and how will we know when we have succeeded?

References

Fuchs, M. 2013. CfP: Rethinking Gamification Workshop [Online]. Germany: Art and Civic Media Lab at the Centre for Digital Cultures, Leuphana University Germany. Available: http://projects.digital-cultures.net/gamification/2013/02/07/118/ [Accessed 15 October 2015].

Rosenzweig, R. & Thelen, D. 2000. The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life, New York, Columbia University Press.

Stuart, K. 2015. Photorealism – the future of video game visuals. The Guardian [Online]. Available: http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/feb/12/future-of-video-gaming-visuals-nvidia-rendering [Accessed 31 October 2015].